Life Before the FDA

Some celebrated the downsizing of the FDA, believing a hostile bureaucracy had been dismantled. Those who understand what it was to live in America before the FDA were decidedly less joyful.

A Dangerous Turning Point at HHS

In early April 2025, under Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services implemented sweeping layoffs that reduced its workforce by approximately 25,000 employees out of a total of 82,000 employees. Critical personnel at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were among those affected.

Notable departures included Dr. Timothy J. Pohlhaus, a leading authority on drug sterility who kept eye drops from blinding the public, and Dr. Peter Stein, director of the Office of New Drugs. Dr. Peter Marks, the nation’s top vaccine regulator, resigned after public disagreements with Kennedy over vaccine safety policies. The layoffs also disrupted programs central to mine safety, infertility research, and smoking cessation.

Some celebrated the downsizing, believing a hostile bureaucracy had been dismantled. Those who understand what it was to live in America before the FDA were decidedly less joyful.

When Breakthroughs Invite Exploitation

By the 1920s, insulin had revolutionized diabetes care, transforming a fatal condition into a manageable one. Children once condemned to starvation diets could now grow up. Yet even after insulin became widely available, it wasn’t immune to competition from unproven alternatives. Thanks to the practice of the traveling salesmen, people could bring their products and claims right to your door.

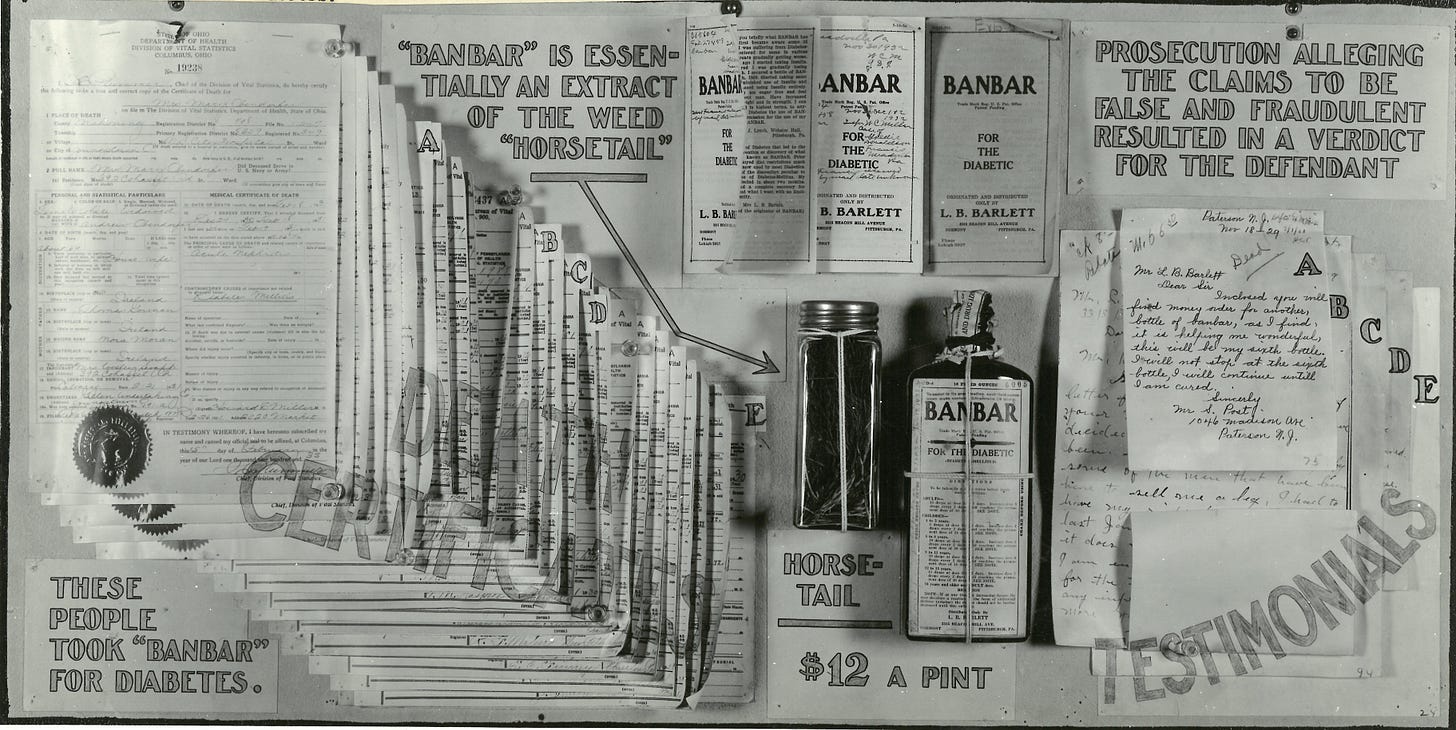

Establishing a personal connection and sharing testimonials of real people is a far better strategy for reaching people compared to delivering statistical analyses and lab results. This was true even when those lab results said a product would kill you, and even when the testimonials came from people who died.

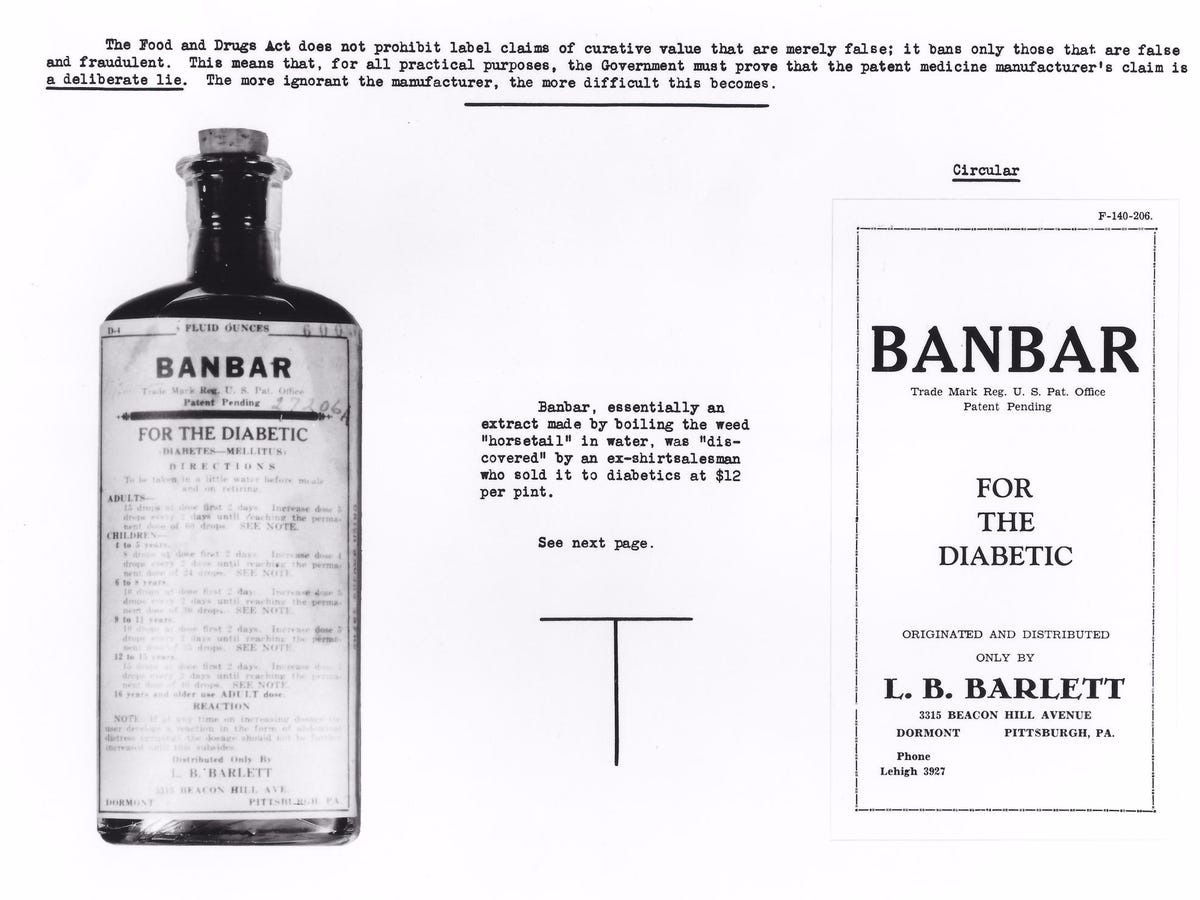

One of the most infamous was Banbar, an ineffective and potentially deadly concoction marketed in the 1930s as a diabetes cure.

Banbar mainly consisted of milk sugar and Equisetum (horsetail)—an herb with no proven efficacy. Patients drawn to the false hope it offered often abandoned insulin, leaving them unprotected against blood sugar spikes. The FDA moved to seize Banbar under the 1912 Sherley Amendment, which barred fraudulent claims, provided that intent to deceive could be demonstrated.

The backlash was swift. Patients and manufacturers cried foul. Why, in a supposedly free country, was a government agency interfering with a product that made people “feel better”? The manufacturer sued the FDA and arrived in court with glowing testimonials from satisfied customers—claims of success, regardless of whether those customers had survived long enough to regret their endorsement.

Evidence, Not Emotion

To counter the testimonials, the FDA launched a grim investigation. Agents tracked down the individuals behind the glowing reviews. They weren’t alive to testify. The agency presented death certificates in place of follow-up reports. Many of Banbar’s so-called success stories had died preventable deaths, having trusted a useless treatment over insulin therapy.

Despite the evidence, the FDA lost the case. The court ruled that, without conclusive proof that the manufacturer intended to deceive, Banbar could not be banned. The product remained on the market.

In a market where it was legal to sell and profit from unproven products that had been shown to kill, it wasn’t long before the FDA was following another trail of deaths. This time, the victims were mostly children.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to InfoEpi Lab to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.